6. October 2010

From the user observation and subsequent interview it is apparent that in real as well as virtual viewpoints a clear comprehension of the orientation in respect to known features is necessary.Real World

In real environments this can be done by referencing known landmarks, comprehending signs or using a map. Other factors could include previous knowledge of the area as in the case of the User Observation. Orientating a map is only possible if:At least one “landmark features” can be recognised in the view and the map, when the current position is known in the real world and map

The observed person could easily identify the current location as well as the rotation of the map to be in the same orientation as the real world through prior knowledge.

The observed person could easily identify the current location as well as the rotation of the map to be in the same orientation as the real world through prior knowledge.

Identifying an unknown feature in the real world first and then trying to locate it on the map by estimating the distance and bearing was not as accurate.

Identifying an unknown feature in the real world first and then trying to locate it on the map by estimating the distance and bearing was not as accurate.

Virtual Tours

In the virtual examples the user observed, he felt that knowing the location and orientation at any time gave him a feeling of confidence and also helped him make decisions where to navigate to next. In Google Street View this is done by a small map, an icon representing the current viewpoint, an arrow as part of that icon showing the viewing direction and arrows in the view itsself.

In Google Street View this is done by a small map, an icon representing the current viewpoint, an arrow as part of that icon showing the viewing direction and arrows in the view itsself.

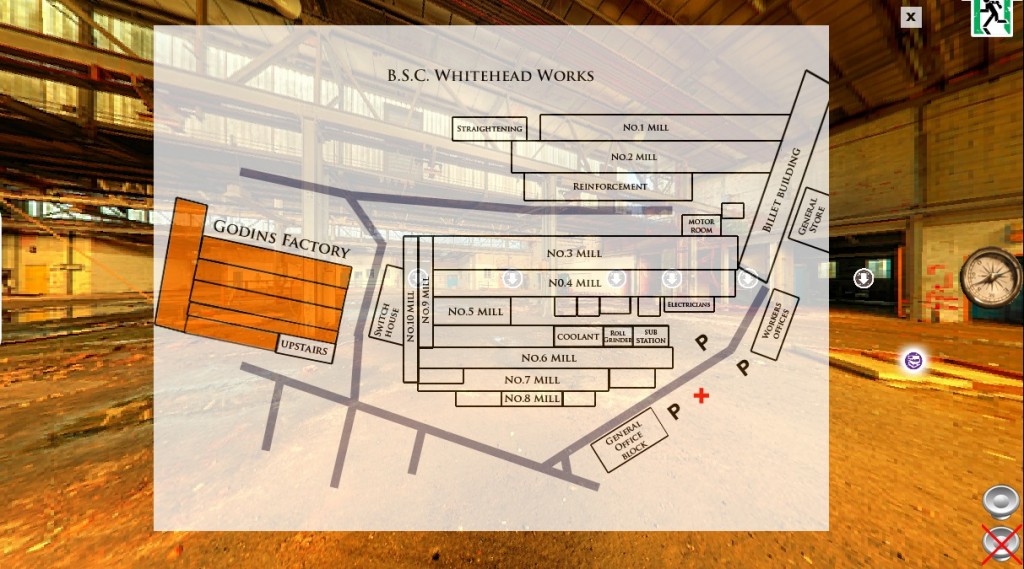

In the second, much simpler, example was a Virtual Tour of a derelict factory. There the map only shows the current location roughly and navigation options are only shown in the view itsself.

This was perceived as negative and gave the user a feeling of unease. A “jump to” dropdown does exist, but was not seen as such by the user indicating an uneffective method.

In the second, much simpler, example was a Virtual Tour of a derelict factory. There the map only shows the current location roughly and navigation options are only shown in the view itsself.

This was perceived as negative and gave the user a feeling of unease. A “jump to” dropdown does exist, but was not seen as such by the user indicating an uneffective method.

References between viewpoints

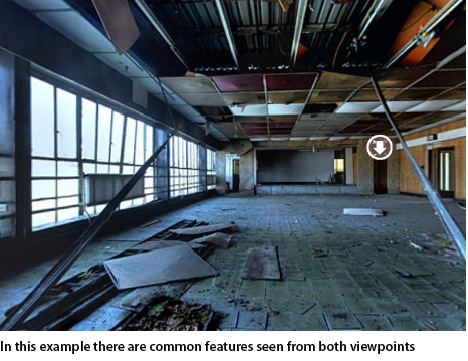

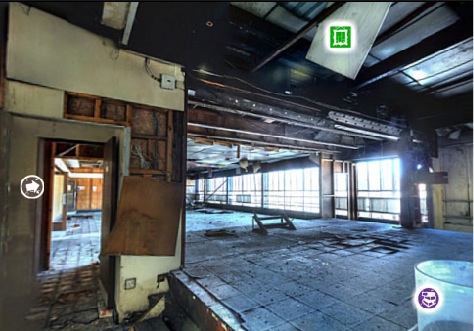

In a virtual tour of an unknown surrounding, the starting point of the virtual tour acts as a reference point for exploration. In the Whiteheads Virtual Tour jumping to the next viewpoint loads that viewpoint at a default orientation irregardless of where the user has come from. This turned out to be very confusing for the user, making him jump back and forth between 2 hotspots before finding his way out.

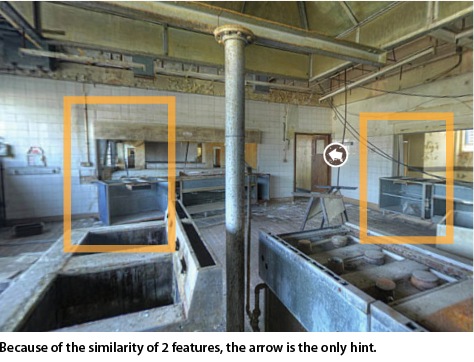

This was enhanced by the fact that features seen in the previous viewpoint could not be seen, as in the following example:

This was enhanced by the fact that features seen in the previous viewpoint could not be seen, as in the following example:

In an immersive environment this feeling of disorientation could be even higher as indicated by experiences by the interviewed user.

In an immersive environment this feeling of disorientation could be even higher as indicated by experiences by the interviewed user.

Analysis: Movement between viewpoints

Probably the main limiting factor for orientation in virtual tours based on photographs is the limitation to a single fixed viewpoint, which can be rotated in full 360 degrees, but no direct movement from this spot is possible. The brain builds up a mental model of the surroundings as we walk to and through spaces. Effectively the user is blindfolded in the process of moving from one viewpoint to the next. Google streetview interpolates between the views by using a motion blur transition in the direction of movement giving a sense of travelling.

Google streetview interpolates between the views by using a motion blur transition in the direction of movement giving a sense of travelling.

In the Whiteheads virtual tour no sense of movement is given and the viewpoints have a simple fade transition.

In the Whiteheads virtual tour no sense of movement is given and the viewpoints have a simple fade transition.